This is a quick note on some thoughts & experiments on fasta parsing, alongside github:RagnarGrootKoerkamp/fasta-parsing-playground.

It’s a common complaint these days that Fasta parsing is slow. A common parser is Needletail (github), which builds on seq_io (github). Another recent one is paraseq (github).

Paraseq helps the user by providing an interface for parallel processing of reads, see eg this example. Unfortunately, this still has a bottleneck: while the users processing of reads is multi threaded, the parsing itself is still single threaded.

1 Minimizing critical sections Link to heading

In Langmead et al. (2018), some approaches are discussed for FASTQ parsing.

- Deferred parsing: search the end of the current block of 4 lines inside a critical section, and then parse those in separate threads.

- Batch deferred: read \(4N\) lines, and then parse those. This reduces contention on the locks.

- Block deferred: read \(B\) bytes, assuming that this exactly matches a single record. This can be done by padding records with spaces to give them all the same size, but is more of a hypothetical best case.

2 RabbitFx: chunking Link to heading

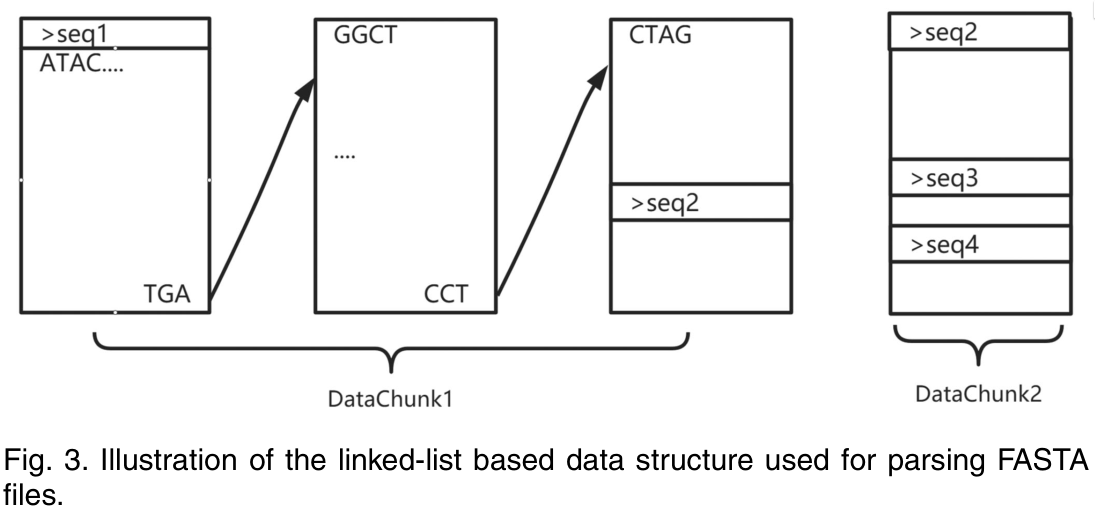

RabbitFx (Zhang et al. 2023) (github) is a recent parser written in C++ that does something new: it splits the entire input file into fixed size chunks (of 8 MB by default) that are distributed those over the threads. Reads that cross chunk boundaries store a link to the next chunk:

Figure 1: The chunking & linking of RabbitFx (Zhang et al. 2023).

The RabbitFx paper then reimplements some basic algorithms on top of this parser and should significantly higher throughput, reaching up to 2.4 GB/s1 for counting bases on a server with two 20-core CPUs, compared to FQFeeder’s 740 MS/s.

Unfortunately, all of this doesn’t work well with gzipped input which requires sequential unzipping. But anyway, I was curious to see how much perf this would give in practice. This can be used as an argument why single-block gzipping is bad.

3 Different chunking Link to heading

In my 1brc post, I took a different approach. When there are \(t\) threads, simply

partition the input file into \(t\) non-overlapping chunks, and give one chunk to

each thread. Then there might be some reads that cross chunk boundaries, but

this is not a problem: each thread first finds the start of the first record

(the first > character), and then processes things from there. Each thread

ends processing when the next > character it runs into is in the next chunk

(or the end of the file is reached).

Figure 2: My proposed chunking: each thread just takes its own slice of the input file and does its own thing. The middle of the three threads processes the reads shown in yellow.

In this model, the parsing does not require any synchronization at all!

In the code, I simply scan for all > characters and then collect a batch of

reads spanning at least 1 MB. Then I send this to a queue to be picked up by a

worker thread.2

In the worker thread, I search the first newline inside each record for the end

of the header, and the rest is the read itself.

Note that the underlying file is memory mapped, so that accessing it in multiple streams is trivial from the code perspective.

4 Experiments Link to heading

I did some experiments both on the CHM13v2.0.fa human genome, and a set of

simulated reads3 from zenodo by Bede Constantinides that are used for

benchmarking Deacon (github).

See the github code for the implementation.

rsviruses17900.fa is 5.4 GB and has reads of average length 2000 bp, and each

read is a single line (ie no linebreaks inside records).

Adding RabbitFx to these benchmarks is still TODO, since I don’t feel like messing with C/C++ bindings at the moment.4

| threads | needletail | paraseq | us |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.91 | 5.28 | 7.81 |

| 2 | 6.95 | 5.09 | 12.46 |

| 3 | 7.04 | 4.97 | 15.26 |

| 4 | 6.81 | 4.63 | 17.27 |

| 5 | 6.84 | 4.70 | 18.32 |

| 6 | 6.82 | 4.66 | 17.83 |

| threads | needletail | paraseq | us |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.77 | bug | 8.26 |

| 2 | 2.80 | 4.01 | 12.24 |

| 3 | 2.80 | 3.96 | 15.38 |

| 4 | 2.78 | 4.02 | 16.30 |

| 5 | 2.80 | 3.92 | 17.08 |

| 6 | 2.77 | 3.96 | 17.28 |

Needletail nor paraseq only allocate a newline-free record on request, which I don’t do in this benchmark, but I believe at least needletail does unconditionally store the positions of all newlines, and so does slightly more work.

The new method caps out at 17 GB/s, while the peak memory transfer rate of my DDR4 RAM5 is around 23 GB/s, so this is not too bad. If I drop the fixed 2.6 GHz CPU frequency that I used for the experiments, instead I get speeds up to 22.7 GB/s, which is actually very close!

Thus, if the throughput of your code on all threads is more than 2-4 GB/s, you might try this technique to avoid file parsing being the point of contention.

5 Outlook Link to heading

I think this is a neat idea, but probably with limited practical usage, since most large inputs will be zipped. And in that case, you may have many input files, and it’s better to spin up one thread/program per input file, so that decompression can be done in parallel.

6 Some helicase benchmarks Link to heading

See https://github.com/imartayan/helicase

Running the helicase benchmarks: cd bench && cargo run -r <path>:

Input files are taken/modified from https://zenodo.org/records/15411280:

| file | what | size | avg len | newlines | distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

rsviruses17900.fa | Viruses | 539 MB | 30 kbp | no | high variance |

rsviruses17900.fastq | Simulated ONT reads | 11 GB | 2 kbp | no | high variance |

rsviruses17900.fasta | (converted to .fasta) | 5.4 GB | 2 kbp | no | high variance |

rsviruses17900.r1.fastq | Simulated Illumina reads | 6.4 GB | 150 bp | no | all same |

rsviruses17900.r1.fasta | (converted to .fasta) | 3.6 GB | 150 bp | no | all same |

chm13v2.0.fasta | human genome | 3.2 GB | 140 Mbp | yes | high variance |

Benchmarks take different inputs:

pathtakes a file path and reads the file.mmaptakes a file path and mmaps the file.sliceandreadertake a&[u8]from an already-read file.

| method | virus | ONT .fq | ONT .fa | Illumina .fq | Illumina .fa | human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| size | 539 MB | 11 GB | 5.4 GB | 6.4 GB | 3.6 GB | 3.2 GB |

| avg record len | 30 kbp | 2 kbp | 2 kbp | 150 bp | 150 bp | 140 Mbp |

| newlines | no | no | no | no | no | yes |

| Regex header (slice) | 15.71 | 20.00 | 9.05 | 18.31 | 0.77 | 20.13 |

| Needletail (file) | 7.44 | 8.73 | 7.16 | 4.07 | 3.13 | 1.89 |

| Needletail (reader) | 8.42 | 11.16 | 8.51 | 4.88 | 3.39 | 2.07 |

| Paraseq (file) | 5.25 | 2.58 | 3.40 | 1.61 | 1.39 | 1.94 |

| Paraseq (reader) | 7.70 | 2.71 | 4.48 | 1.90 | 1.66 | 2.29 |

| Header only (file) | 6.73 | 6.99 | 6.07 | 5.25 | 3.75 | 4.48 |

| Header only (mmap) | 8.56 | 9.12 | 8.90 | 6.55 | 5.72 | 5.69 |

| Header only (slice) | 8.70 | 11.60 | 7.92 | 8.59 | 5.42 | 6.02 |

| DNA string (file) | 4.71 | 5.91 | 4.63 | 4.81 | 3.24 | 2.89 |

| DNA string (mmap) | 5.53 | 9.10 | 5.92 | 6.61 | 3.85 | 3.42 |

| DNA string (slice) | 5.47 | 11.60 | 5.08 | 8.59 | 3.52 | 3.23 |

| DNA packed (file) | 3.33 | 4.42 | 3.15 | 3.16 | 2.22 | 2.00 |

| DNA packed (mmap) | 4.03 | 5.03 | 3.98 | 3.35 | 2.57 | 2.35 |

| DNA packed (slice) | 3.77 | 5.32 | 3.55 | 3.64 | 2.40 | 2.18 |

| DNA columnar (file) | 3.62 | 4.62 | 3.45 | 3.73 | 2.67 | 2.45 |

| DNA columnar (mmap) | 4.16 | 5.59 | 4.17 | 4.13 | 2.96 | 3.06 |

| DNA columnar (slice) | 3.66 | 5.89 | 3.50 | 4.57 | 2.64 | 2.78 |

| DNA len (slice) | 6.37 | 6.27 | 5.84 | 4.60 | 4.50 | 4.69 |

Observations:

- Helicase is much faster for fastq than for fasta, surprisingly, both for

&strand columnar/packed output. - For fastq, helicase is best.

- For short reads, helicase is best (less per-record overhead).

- For fasta with newlines, helicase is slower than on no-newline data, but faster than needletail/paraseq.

- Needletail is quite good, but slow on short reads and human data with newlines.

- Paraseq is only comparable in speed for long chromosomes.

- In all cases, processing an in-memory

&[u8]is faster than file input. mmapis faster than usual file parsing, but usually (not always) slower than bytes from memory.

We can modify our mmap-based multithreading to call helicase (slice input, string output) instead of our stub parser in each thread, as in this code. Note that we simply split the input into 6 chunks (one for each thread) and ignore cross-chunk reads in helicase.

Recall that our baseline simply searches for > characters and then for the

first following \n to determine the end of the header, and does nothing else.

| method | threads | virus | ONT .fq | ONT .fa | Illumina .fq | Illumina .fa | human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| size | 539 MB | 11 GB | 5.4 GB | 6.4 GB | 3.6 GB | 3.2 GB | |

| avg record len | 30 kbp | 2 kbp | 2 kbp | 150 bp | 150 bp | 140 Mbp | |

| newlines | no | no | no | no | no | yes | |

| us (count-only) | 6 | 27.1 | 26.2 | 25.8 | 15.9 | 16.9 | 23.0 |

| helicase slice default | 6 | 20.9 | 24.5 | 21.8 | 20.8 | 20.4 | 10.9 |

| us (count-only) | 3 | 24.5 | 22.5 | 20.7 | 14.1 | 16.1 | 22.0 |

| helicase slice default | 3 | 13.6 | 19.5 | 13.4 | 15.5 | 12.0 | 8.0 |

| us (count-only) | 1 | 14.3 | 11.8 | 16.18 | 7.76 | 8.97 | 12.22 |

| helicase slice default | 1 | 5.5 | 8.7 | 5.94 | 6.42 | 4.03 | 3.43 |

| Needletail | 1 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 8.68 | 4.30 | 4.47 | 3.22 |

| Paraseq | 1 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 4.80 | 3.33 | 2.75 | 3.79 |

| helicase path default | 1 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 4.44 | 4.48 | 3.09 | 3.16 |

| helicase path ignore | 1 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 6.27 | 5.94 | 4.28 | 5.12 |

| helicase path header | 1 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 6.15 | 5.31 | 3.82 | 5.00 |

| helicase path string | 1 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 4.55 | 4.75 | 3.25 | 3.24 |

| helicase path columnar | 1 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 3.46 | 3.65 | 2.66 | 2.77 |

| helicase path packed | 1 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 2.83 | 3.13 | 2.28 | 2.16 |

Observations:

- Our trivial method is already saturated at 3 threads.

- Helicase needs the full 6 threads for reads and viruses.

- Helicase is quite a bit slower on the line-breaked human data, probably because it does a lot of additional (and mostly inevitable) I/O.

- Needletail is quite fast in all single-threaded cases (but note that we do not

call

.seq()).

References Link to heading

I haven’t looked into the details of their code, but this really is not so fast. As a baseline, SimdMinimizers computes minimizers at over 500 MB/s on a single core, and that is much more involved that simply counting the number of A/C/G/T characters. ↩︎

Really the queue isn’t needed so much here – we could just pass a callback to a worker function, similar to what paraseq does with the map-reduce model. Then, each thread simply processes its own data. ↩︎

Download

rsviruses17900.fastq.gz, unzip, and then convert the.fastqto a.fa. ↩︎I get build errors on the

Examples.cpp. Thanks C++. ↩︎Note that the file is read from RAM, not disk/SSD, since it’s already cached by the kernel. ↩︎