- 1 Construction of k-PHF using modified PtrHash

- 2 k-PHF Lower bounds

- 3 Cache-optimal k-PHF

- 4 RecSplit

- 5 What is the optimal bin-size distribution for PtrHash-based k-PHF

- 6 Halfway bin-size for \(k=2\)

- 6.1 First half

- 6.2 Second half

- 6.3 Total

- 6.4 First-half optimum

- 7 Optimal bin-size distribution

- 8 Optimal choice of seed

- 9 Practical idea?

There are ongoing notes on lower and upper bounds for non-minimal k-perfect hashing based on discussions with Stefan Walzer, Stafan Hermann, and Peter Sanders.

1 Construction of k-PHF using modified PtrHash Link to heading

Code at src/kphf.rs at http://github.com/RagnarGrootKoerkamp/static-hash-sets

slot_ratio: number of slots to use relative to \(n\).meta_ratio: size of metadata relative to total input size.sort: sort the buckets by size or not?

Results for \(k=16\):

| |

Conclusion: we can construct k-PHF with 20% extra slots and 0.1% relative size of the metadata.

Thus, for \(\alpha=1/1.2 = 0.83\), we can get 0.064 bits/key. Pushing it a bit more, with meta_ratio down to 0.00085 we get 0.0544 bits/key when using consensus. I can now not reproduce the 0.0320 bits/key bottom rows of the table anymore.

The corresponding lower bound (see script below) is 0.0362, which indeed is above the 0.0320.

2 k-PHF Lower bounds Link to heading

For minimal k-PHF, the brute-force solution admits \(\binom{n}{k,\dots,k}\) solutions, so needs \((n/k)^n / \binom{n}{k,\dots,k}\) tries, which corresponds to \(\log e + \log((k!)^{1/k} / k)\) bits.

For load factor \(\alpha\), this script computes the lower bound for non-minimal $k$-PHF.

| load \(\alpha\) | k=1 | k=2 | k=4 | k=8 | k=16 | k=32 | k=64 | k=128 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.07466 | 0.00849 | 0.00022 | 0.0000003 | 0.000000000001 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.15498 | 0.03112 | 0.00259 | 0.00004 | 0.00000002 | 0.00000000000002 | ||

| 0.3 | 0.24202 | 0.06581 | 0.00989 | 0.00052 | 0.000003 | 0.0000000004 | ||

| 0.4 | 0.33724 | 0.11221 | 0.02444 | 0.00267 | 0.00008 | 0.0000002 | 0.000000000003 | |

| 0.5 | 0.44269 | 0.17114 | 0.04833 | 0.00857 | 0.00068 | 0.000012 | 0.000000009 | 0.00000000000001 |

| 0.6 | 0.56140 | 0.24472 | 0.08410 | 0.02095 | 0.00318 | 0.00020 | 0.000002 | 0.0000000006 |

| 0.7 | 0.69828 | 0.33704 | 0.13568 | 0.04360 | 0.01028 | 0.00149 | 0.00009 | 0.0000009 |

| 0.8 | 0.86221 | 0.45624 | 0.21044 | 0.08294 | 0.02699 | 0.00677 | 0.00113 | 0.00009 |

| 0.9 | 1.07359 | 0.62179 | 0.32631 | 0.15418 | 0.06498 | 0.02404 | 0.00755 | 0.00188 |

| 1.0 | 1.44269 | 0.94265 | 0.58893 | 0.35509 | 0.20832 | 0.11967 | 0.06761 | 0.03770 |

2.1 Estimated lower bounds for variants Link to heading

\(k=8\):

- regular: 0.36

- windowed: 0.08

- 4-aligned: 0.13

\(k=16\):

- regular: 0.21

- windowed: 0.02

- 4-aligned: 0.05

3 Cache-optimal k-PHF Link to heading

Given \(n\), \(k\), and \(\alpha\), one can optimize two different things:

- The overall size of the MPHF

- The number of queries answered by a fixed-size cache.

These are different! For eg bucket-placement techniques, you want to balance the size of the bins as much as possible to ensure there are sufficient empty bins until the end. Whereas in order to answer as many keys as possible using the cache, you would rather have a very unbalanced bin size distribution and then use more space afterwards to work around this.

4 RecSplit Link to heading

RecSplit takes the keys and repeatedly splits it into parts until only parts of size (at most) \(k\) remain. The original RecSplit already provides a minimal k-PHF when \(k\) is a power of \(2\). It has \(O(1)\) overhead per split when each split is encoded independently, and smaller overhead when consensus is used. Note that the shape of the splitting tree does not matter: it can be either ‘repeatedly split off the bottom \(k\)’ or repeatedly ‘split in half’.

Strategies for splitting off the bottom \(k\):

4.1 Accept \(\leq k\) Link to heading

Choose a \(\lambda\). Then hash all keys and accept each with probability \(\lambda / n\). Accept the bin when the size \(\mathrm{Po}(\lambda) \leq k\). Choose \(\lambda\) such that the expected size of the truncated distribution equals the average load \[\mathbb E[\mathrm{Po}(\lambda)_{\leq k}] = \alpha k.\] The problem is that this needs many tries when \(\alpha \to 1\).

Instead, do the following: accept the bin only when it has size between \(k-x\) and \(k\) inclusive, for some integer \(x\) depending on \(\lambda\) such that the expected size is (roughly) \(\alpha\). To make this work exactly, accept \(k-x\) itself only with some probability. Then choose \(\lambda\) such that the probability of accepting the bin is maximized.

This script does something similar, but only considers a ‘backlog’ of previously unplaced keys for each bin, rather than all keys. It gets reasonably close (within 30% or so) of the lower bound:

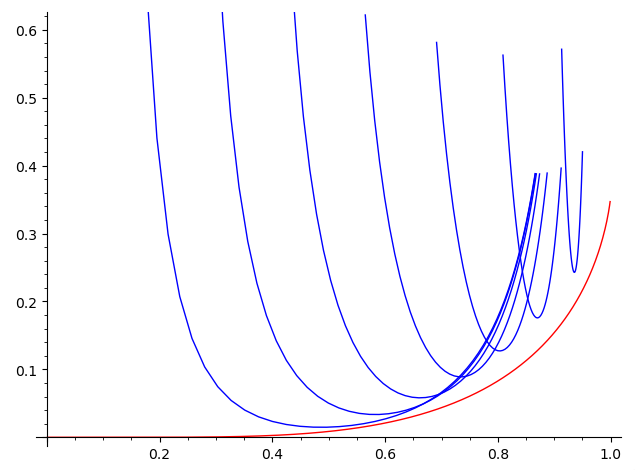

Figure 1: red: space usage of $α$-PHF for (k=8). Blue: space usage of the greedy ‘backlog’ strategy for various parameters.

With consensus, this should also have quite small overhead.

5 What is the optimal bin-size distribution for PtrHash-based k-PHF Link to heading

At the end, the bins follow some size distribution. When bruteforcing a seed, this is simply a truncated Poisson distribution with expected value \(\alpha k\).

When choosing a seed, we should choose the one that makes the distribution most /flat//uniform, with respect to some metric.

We considered the case \(k=2\) and the optimal distribution of bin-sizes after half the keys have been places. When halfway through all bins have size \(1\), we basically build two MPHFs on \(n/2\) keys, for 1.4 bits/key overall.

When halfway through half the buckets have 2 keys, we sort-of build a $k=2$-MPHF on the first and second half of keys. For the first half we select \(n/2\) ‘random’ buckets which saves \(n/2\) bits, but then pay \(n/2\) bits to actualy map into them. (Thus, building a $2$-MPHF on \(n/4\) bins is exactly as hard as building a $2$-PHF with bins of size \(0\) or \(2\) on \(n/2\) bins.) The second half of keys needs \(n/2\) extra bits to map into the gaps left behind by the first half. In the end, this uses 1.4 bits/key as well.

So, the optimal choice must be to have somewhere between \(0\) and \(n\) bins of size \(1\) halfway through.

5.1 Optimal bucket bunction for minimal k-PHF Link to heading

See Hermann et al. (2025):

- github:stefanfred/engineering-k-perfect-hashing/…/OptimalBucketFunction.hpp

- github:stefanfred/engineering-k-perfect-hashing/…/muericalIntegrationBucketFunction.cpp

6 Halfway bin-size for \(k=2\) Link to heading

Suppose we are incrementally building a $2$-MPHF on \(n\) keys. At some point, we have assigned half the keys, and at that point there are \(a\) bins of size 2, \(b\) bins of size 1, and \(c\) bins of size 0, with \(a+b+c=n/2\) (the total number of bins) and \(2a+1b+0c=n/2\) (half the keys). This implies \(a=c=(n/2-b)/2\). Now say we have \(b=\beta n/2\) of the bins with 1 key in them. We want to derive 2 numbers:

- The entropy/bits/space needed to map first half of keys.

- The space needed to map the second half of keys.

and from this we get the space needed for all keys.

6.1 First half Link to heading

We first choose the bins we are going to use: \[A:=\binom{n/2}{a,b,c}\] Then, we choose exactly which keys go into each bin: \[B:=\binom{n/2}{\underbrace{2,\dots, 2}_{a\times}, \underbrace{1,\dots, 1}_{b\times}}\] The total number of functions mapping the first half of keys into the \(n/2\) bins is \[N:=(n/2)^{n/2}.\] We compute the number of bits per element needed to store a suitable function for the first half as \[S_1:=\frac 1n \log \frac{N}{AB} = \frac 12 \log e - \frac 14(1-\beta) - \frac 12 H(\beta)\] where \(H(x) = - x\log(x) - (1-x)\log(1-x)\) is the entropy of \(\beta\).

(Note that I’m normalizing by \(\frac 1n\) here, so this is bits/key over all \(n\) keys.)

6.2 Second half Link to heading

The bins that the keys go to are now fixed. So the number of suitable functions is \[C:=\binom{n/2}{\underbrace{2,\dots, 2}_{c\times}, \underbrace{1,\dots, 1}_{b\times}}\] which equals \(B\) since \(a=c\).

The total number of functions for the second half is again \(N\). We then get \[S_2:=\frac 1n \log \frac{N}{C} = \frac 12 \log e + \frac 14 (1-\beta).\]

6.3 Total Link to heading

The \(\frac 14(1-\beta)\) terms cancel, and the total space is \[S:=S_1+S_2=\log e - \frac 12 H(\beta)\]

Thus, \(\beta=0\) and \(\beta=2\) both require \(\log e\) bits/key, corresponding to our earlier analysis. Optimal is \(\beta=1/2\), ie half the bins having 1 element, where the total space usage is \(\log e - \frac 12\) which indeed is exactly the optimal space usage of a 2-MPHF.

A property of \(\beta=1/2\) is that then, the number of keys in size-1 bins exactly equals the number of keys in size-2 bins. But those do not equal the number of keys in size-0 bins, so this feels slightly ad-hoc I’d say.

6.4 First-half optimum Link to heading

Note that the \(\beta=\frac 12\) that minimizes the overall space is not the same as the one that minimizes the space for the first half. That, instead, is at \(\beta = \sqrt 2 - 1 \approx 0.414\) (wolfram alpha) with value \[S_1(\sqrt 2 - 1) = 0.0855 \textrm{ bits/key}\] whereas with the globally optimal value we have \[S_1(1/2) = \frac 12 \log e -\frac 18 - \frac 12 = 0.0963 \textrm{ bits/key}\] which is slightly more, but not too much.

The total memory in these two cases is: \[S(\sqrt 2-1) = 0.9533\] and \[S(1/2) = 0.9426\]

Summarizing:

| \(\beta\) | \(S_1\) | \(S = S_1+S_2\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(\sqrt 2-1\) | 0.0855 | 0.9533 |

| \(1/2\) | 0.0963 | 0.9426 |

| diff | 0.0108 | -0.0107 |

Curiously, the space we save at the halfway point is (almost?) exactly (up to rounding errors?) the space we then loose overall.

7 Optimal bin-size distribution Link to heading

Based on the above, note that at the halfway point, \(\beta = 1/2\) gives 25% bins of size 0, 50% bins of size 1, and 25% bins of size 2. That is exactly the binomial distribution! Thus, we hypothesize that, if the goal is to reach \(\alpha=1\), at any point in time, the distribution of bin-sizes should follow a binomial distribution.

Equivalently: the probability of putting a key in a bin should scale with the number of empty slots in the bin. (Nice edge case: empty bins then have probability 0.) Or: for each key we choose a random empty slot, rather than a random bin.

Another way of looking at this: if at some point the \(B\) bins have \(s_1, \dots, s_B\) empty slots remaining (for \(S=s_1+\dots+s_B\) remaining keys), the total number of remaining good functions that works is \(G:=\binom{S}{s_1, \dots, s_B}\), out of \(T:=(n/B)^{S}\) functions in total. The number of tries to find a good function is then \[ T/G = \frac{(n/B)^S}{\binom{S}{s_1,\dots, s_B}} = \frac{(n/B)^S}{S!} \prod_i s_i! \] Thus, we want to minimize the cost//badness/ \(\prod s_i\).

Specifically, if we have some current badness \(b\) and we have a seed for a bucket with \(\ell\) keys that puts them in (distinct) bins with \(s^1, \dots, s^\ell\) remaining free slots, the badness goes down by \(\prod s^i\), and so we want to choose a seed that maximizes this product.

Unfortunately, using this cost function in my k-PHF variant of PtrHash does not seem to work too well, and it causes more collisions than simply choosing the seed that (lexicographically) minimizes the number of largest buckets it hits.

8 Optimal choice of seed Link to heading

How many bits/key do we need? Then derive bucket function from that.

- Place 1 key at a time.

- Butting it in a bucket with \(s\) empty slots (relatively) reduces the hardness by \(s\times\), when aiming for minimal k-PHF in the end.

- We can spend 1 bit to put a key in a bucket with 2x more empty slots.

- Choose a seed that optimizes

entropy(seed) + entropy(remaining work). - Somehow encode all these seeds efficiently. To use consensus we’d need to actually consider multiple tries for each seed.

9 Practical idea? Link to heading

Inspired by IcebergHT (Pandey et al. 2023), see this post on hash table bounds for a screenshot.

- We make buckets of 64 elements.

- We store a 64-byte (single-cache line) filter for each bucket, containing an 8-bit

fingerprint for each element.

- This allows much larger k than if we store key-value pairs inline directly.

- With 64-bit keys and 64-bit values, we’d pretty much need 2 cache misses anyway?

- Rather than falling back to secondary structures, as in IcebergHT, we put a

64-PHF in front of this. See table at the top for space bounds. At 90% load:

0.0075 bits/elem, or 2MB metadata for a 16GB array of 64bit total key-value pairs.

- As usual when using a bucket function, almost all queries will be answered using a small prefix anyway.

Drawback: 64 8-bit fingerprints has 25% false-positive rate for both positive and negative queries. We could try something like storing the EF encoding of 60 10-bit fingerprints?

- Store 8 bits explicitly

- Store 128bit 01 mask with unary encoding of how often a multiple of 256 is crossed.

Even stronger:

- map 128 keys to a cache line, and store 4-bit fingerprints + another 4 bits using EF.

- Since the keys are sorted by fingerprint, we roughly know where to look, and so we can start probing from the expected location outwards.