Research Proposal: Near-linear exact pairwise alignment Link to heading

Abstract Link to heading

Pairwise alignment and edit distance specifically is a problem that was first stated around 1968 (Needleman and Wunsch 1970; Vintsyuk 1968). It involves finding the minimal number of edits (substitutions, insertions, deletions) to transform one string/sequence into another. For sequences of length \(n\), the original algorithm takes \(O(n^2)\) quadratic time (Sellers 1974). In 1983, this was improved to \(O(ns)\) for sequences with low edit distance \(s\) using Band-Doubling. At the same time, a further improvement to \(O(n+s^2)\) expected runtime was presented using the diagonal-transition method (Ukkonen 1983, 1985; Myers 1986).

Since then, the focus has shifted away from improving the algorithmic complexity and towards more efficient implementations of the algorithms, using e.g. bit-packing, delta-encoding, and SIMD (Myers 1999; Šošić and Šikić 2017; Suzuki and Kasahara 2018).

Meanwhile, the edit distance problem was also generalized to affine costs (Gotoh 1982), which is a biologically more relevant distance metric when computing the distance between DNA sequences. It appears that the \(O(n+s^2)\) diagonal transition algorithm was mostly forgotten, until recently it was generalized to also handle affine costs and implemented efficiently in WFA and BiWFA (Marco-Sola et al. 2021, 2023). This has sparked new interest in pairwise alignment from the field of computational biology, and makes it possible to align significantly longer sequences provided they have a sufficiently low error rate.

In this PhD, I first want to thoroughly understand existing algorithms, their implementations, and their performance characteristics on various types of data. Then, the goal is to design efficient near-linear exact global pairwise alignment algorithms by building on the A* framework first introduced in Astarix (Ivanov et al. 2020; Ivanov, Bichsel, and Vechev 2022) and combining this with the implementation efficiency of WFA and Edlib.

A*PA has already shown over \(200\times\) speedup over these tools on \(10^7\) bp long sequences with uniform errors. However, on alignments with long indels or too high error rate A*PA is currently slower because it needs \(\sim 100\times\) more time per visited state than SIMD-based approaches. Future iterations are expected to decrease this gap and lead to an aligner that outperforms state-of-the-art methods by at least \(10\times\) on various types of data.

Introduction and current state of research in the field Link to heading

Computing edit distance is a classic problem in computer science and Needleman-Wunsch (Needleman and Wunsch 1970; Sellers 1974) is one of the prime examples of a dynamic programming (DP) algorithm. This problem naturally arises in bioinformatics, where it corresponds to finding the number of biological mutations between two DNA sequences. In this setting, the problem is usually referred to as pairwise alignment, where not only the distance but also the exact mutations need to be found. As such, biological applications have always been a motivation to develop faster algorithms to solve this problem:

- the original \(O(n^2)\) Needleman-Wunsch algorithm (Needleman and Wunsch 1970; Sellers 1974) that is quadratic in the sequence length \(n\);

- the \(O(ns)\) Dijkstra’s algorithm that is faster when the edit distance \(s\) is small;

- the \(O(ns)\) band-doubling algorithm (Ukkonen 1985) that allows a much more efficient implementation;

- the even faster \(O(n+s^2)\) expected runtime diagonal-transition algorithm (Ukkonen 1985; Myers 1986).

The biological application has motivated a generalization of the edit distance problem to affine gap-costs (Waterman, Smith, and Beyer 1976; Gotoh 1982; Marco-Sola et al. 2021), where the cost of a gap of length \(k\) is an affine (as opposed to linear) function of \(k\), i.e. \(open + k\cdot extend\). This better models the relative probabilities of biological mutations.

In recent years DNA sequencing has advanced rapidly and increasingly longer DNA sequences are being sequenced and analysed. Now that so called long reads are reaching lengths well over \(10k\) base pairs, even up to \(100k\) bp for some sequencing techniques, the classical quadratic algorithms do not suffice anymore. This has caused a few lines of research:

- The Needleman-Wunsch and band-doubling algorithms have been improved using bit-packing and delta encoding, where multiple DP states are stored and computed in a single computer word (Myers 1999; Suzuki and Kasahara 2018), as implemented by Edlib (Šošić and Šikić 2017).

- Advances in hardware have further enabled more efficient implementations of the existing algorithms using better data layouts and SIMD, as used by Parasail (Daily 2016), WFA (Marco-Sola et al. 2021), WFA-GPU (Aguado-Puig et al. 2022), and block aligner (Liu and Steinegger 2023).

- Many inexact (heuristic) methods have been proposed to speed up alignment significantly, at the cost of not having a guarantee that the returned alignment is optimal.

Despite these advances, the fastest exact pairwise alignment algorithms still scale quadratically with sequence length on data with a constant error rate.

My research starts with the recent introduction of A* to sequence-to-graph alignment (Ivanov, Bichsel, and Vechev 2022; Ivanov et al. 2020). We applied similar ideas to pairwise alignment, and it turns out that A* with some additional techniques is able to lower the runtime complexity from quadratic to near-linear on sequences with a low uniform error rate (Groot Koerkamp and Ivanov 2024).

Goals of the thesis Link to heading

Here I list the main goals of this thesis. They are discussed in more detail in Detailed work plan.

The main goals of this thesis fall into two categories:

- Comparing existing methods

- Understand, analyse, and compare existing

alignment algorithms, implementation techniques, and tools.

Theory: Conceptually understand existing algorithms and techniques.

First, I want to obtain a thorough understanding of all existing algorithms and implementations on a conceptual level. As listed in the introduction, there are multiple different existing algorithms (DP, Dijkstra, band-doubling, diagonal-transition), and each come with their own possible optimizations (SIMD, difference-recurrences, bit-packing).

Practice: Benchmark existing tools/implementations on various types of data.

Secondly, a thorough benchmark comparing these algorithms and implementations does currently not exist, but is needed to understand the trade-offs between techniques and alignment parameters and improve on the state-of-the-art.

Visualization: Visualize new and existing algorithms.

Visualizations make algorithms much easier to understand, explain, and teach, and can even help with comparing performance of difference methods and debugging.

- New methods

- Develop A*PA, a new near-linear algorithm and implementation for exact

pairwise alignment that is at least \(10\times\) faster than other methods on most types

of input data.

- A*PA v1: initial version: Apply the seed heuristic of Astarix (Ivanov, Bichsel, and Vechev 2022) to exact global pairwise alignment and extend it with chaining, gap-costs, pruning, and diagonal-transition.

- A*PA v2: efficient implementation: Speed up the implementation using SIMD. This merges ideas from block aligner (Liu and Steinegger 2023) and global band-doubling (Ukkonen 1985) into local column- or block-based doubling.

- Scope: affine costs: Generalize the scope to affine-cost alignments. This will require new ways to efficiently compute the heuristic due to the more complex cost-model.

- Scope: ends-free alignment and mapping: Support semi-global and extension alignment, and support efficiently aligning multiple reads against a single reference.

- Further extensions: A non-admissible heuristic could lead to faster approximate algorithms. Alternatively, a guessed inexact alignment could speed up finding a correct alignment or proving it is correct.

Lastly, there are many other interesting problems such as assembly, RNA folding, and possibly applying pruning to real-world route planning, which fall in a category of open ended research, if time permits.

Impact Link to heading

Many types of pairwise alignment are used in computational biology. Many inexact (heuristic) approaches have been developed to keep alignments sufficiently fast given the increasing size of sequences that are being aligned and the increasing amount of biological data available. A faster exact algorithm reduces the need to fall back to inexact methods, and reduces the need to accept the possibility of suboptimal alignments.

Progress to date Link to heading

Theory: Reading the existing literature has lead to multiple blogs posts collecting information and ideas. This includes a systematic overview (curiouscoding.nl/posts/pairwise-alignment) of over 20 algorithms and papers on pairwise alignment, including a table comparing them and illustrations of the parameters and algorithms.

The literature also sparked multiple ideas and smaller observations regarding WFA:

- I suggested using divide and conquer (Hirschberg 1975) for WFA, which turned out to be already in development as BiWFA, and found a related bug in the preprint (Marco-Sola et al. 2023).

- Ideas to reduce the memory usage by WFA and other algorithms needed for tracebacks. In essence, the tree of paths to the last front is very sparse, and typically requires much less memory to store than the full set of wavefronts.

- Some further notes regarding variants of the recursion, reducing the number of visited states, and an improved way to handle match bonus.

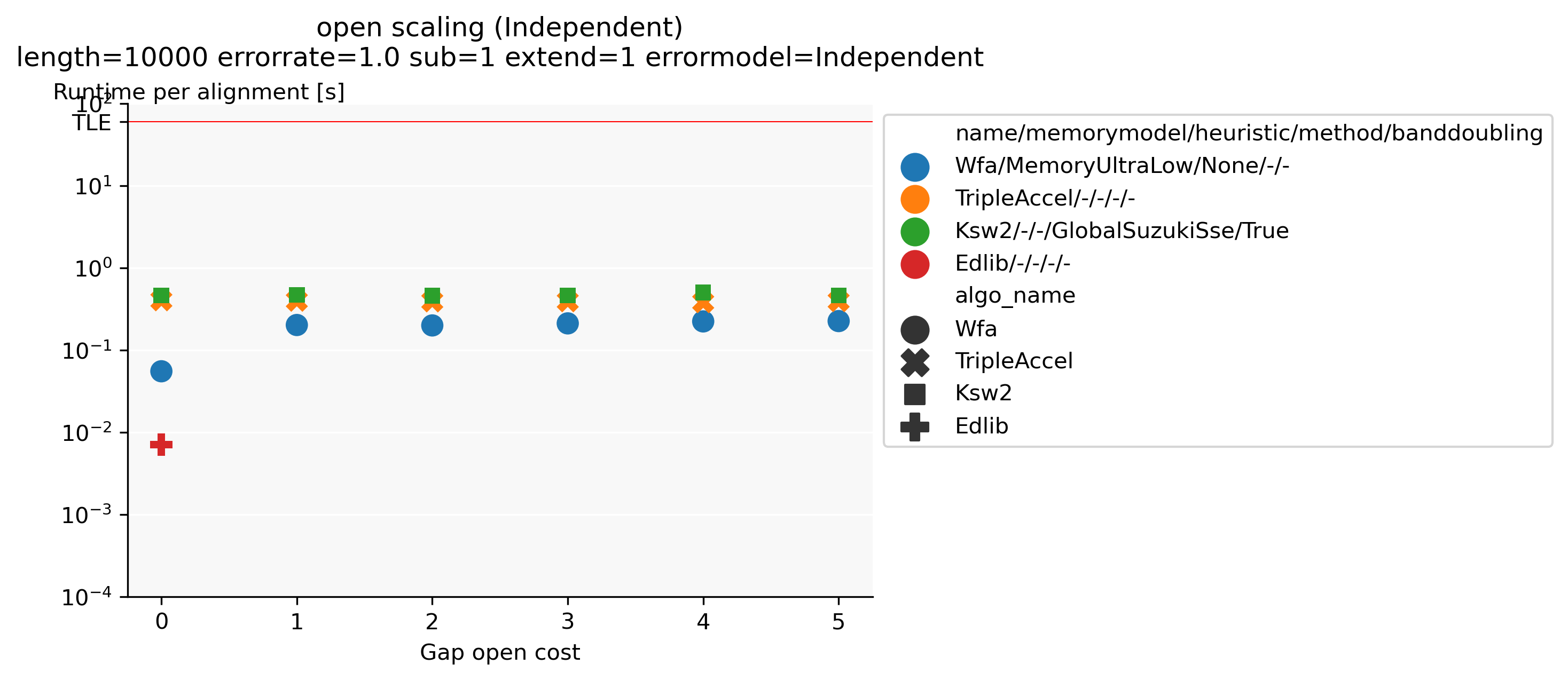

Benchmarking: Together with Daniel Liu, I developed PaBench (github.com/pairwise-alignment/pa-bench), a tool to help benchmarking pairwise aligners. It provides a uniform interface to many existing aligners as part of the runner binary, and contains an orchestrator that can run a large number of alignment jobs as specified via a YAML configuration file. Possible configuration options are selecting the datasets to run on (files, directories, generated data, or downloaded data), which cost-model to use, and which aligners to run and their parameters. This makes it very quick and easy to generate plots such as Figure 1, showing that when aligning unrelated/independent sequences Edlib for unit-cost alignments is around \(30\times\) faster than any affine alignment that includes a gap-open cost.

Figure 1: Runtime comparison between different aligners when aligning two complete independent random sequences, for various gap-open costs. The substitution and gap-extend cost are fixed to 1. Edlib only supports a gap-open cost of (0).

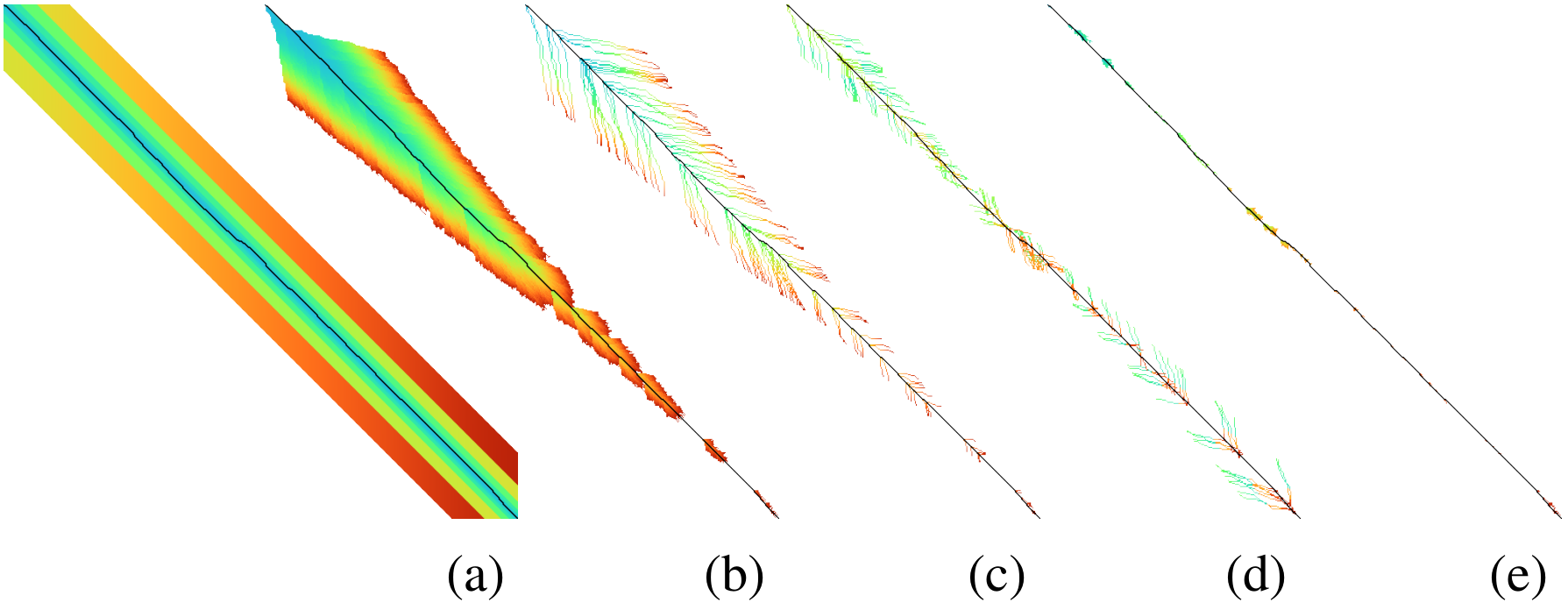

Visualization: I wrote a visualizer to show the inner workings of A*PA and to help with debugging. The existing Needleman-Wunsch, band-doubling, and diagonal-transition algorithms were re-implemented to understand their inner workings and to make for easy visual comparisons, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Visualizations of (a) band-doubling (Edlib), (b) Dijkstra, (c) diagonal-transiton (WFA), (d) diagonal-transition with divide-and-conquer (BiWFA), and (e) A*PA.

A*PA v1: The first version of A*PA has been implemented at github.com/RagnarGrootKoerkamp/astar-pairwise-aligner and is evaluated in a preprint (Groot Koerkamp and Ivanov 2024). The current codebase implements the following techniques:

- seed heuristic (Ivanov, Bichsel, and Vechev 2022), the basis for the A* search,

- match-chaining to handle multiple matches,

- gap-costs, to account for gaps between consecutive matches (not yet in preprint),

- inexact matches, to handle larger error rates,

- match-pruning, penalizing searching states that lag behind the tip of the search,

- diagonal-transition, speeding up the search by skipping over states that are not farthest-reaching (not yet in preprint).

Together this has already shown promising results with linear runtime scaling on sequences with a low uniform error rate, resulting in up to \(250\times\) speedup over other aligners for sequences of length \(10^7\) bp (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Runtime scaling of A*PA with seed heuristic (SH) and chaining seed heuristic (CSH) on random sequence-pairs of given length with constant uniform error rate (5%).

Detailed work plan Link to heading

The work is split over the following \(9\) concrete projects, ordered by estimated order of completion.

WP1: A*PA v1: initial version Link to heading

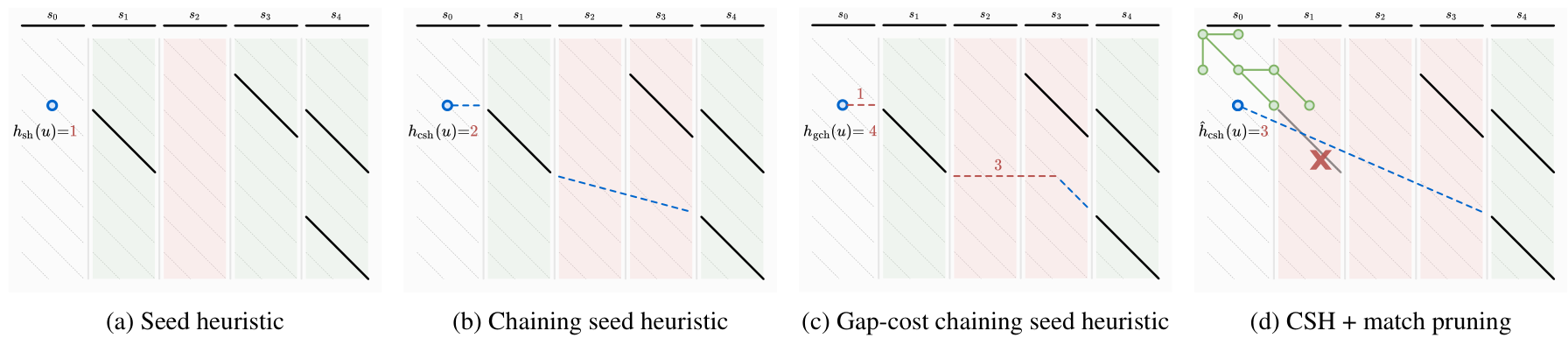

A*PA (Groot Koerkamp and Ivanov 2024) introduces the seed heuristic of Ivanov, Bichsel, and Vechev (2022) (Figure 4 a) that provides a lower bound on the edit distance between (the suffixes of) two sequences by counting the number of seeds without matches: for each seed (disjoint substring of sequence \(A\)) that does not occur in sequence \(B\), there must be at least \(1\) edit to turn \(A\) into \(B\).

Figure 4: The different heuristics and techniques introduced by A*PA.

A*PA extends this in a few ways. See the preprint for more details.

- First, it introduces inexact matches, where a match is considered to be any substring of \(B\) that less than distance \(r\) away from the seed. This allows the A* to efficiently handle larger error rates.

- The chaining seed-heuristic (b) requires seed-matches to be in the same order in \(B\) as in \(A\). This way, spurious matches have less negative effects on the value of the heuristic.

- The gap-cost chaining seed heuristic (c) additionally penalizes the cost that must be made for indels between matches that are on different diagonals.

- Pruning (d) is an additional technique that penalizes searching behind the tip of the search. As soon as the start of a match is expanded, the match is not needed anymore and can be removed. This makes the heuristic inadmissible, but we prove that A* is still guaranteed to find an optimal path.

- Lastly, we use an optimization similar to diagonal-transition so that only farthest-reaching states are expanded by the A*.

This results in near-linear scaling (Figure 3) when aligning long sequences with low constant uniform error rate, leading to \(250\times\) speedup over state-of-the-art aligners WFA and Edlib.

Status: This work package is almost done and will be submitted to BioInformatics soon.

WP2: Visualizing aligners Link to heading

There are many existing algorithms for pairwise alignment, many of which are more than 30 years old. Some papers (Ukkonen 1985; Liu and Steinegger 2023) contain manual figures depicting the working of an algorithm, but other papers do not (Šošić and Šikić 2017; Marco-Sola et al. 2021). This limits the quick intuitive understanding of such algorithms. Since pairwise alignment happens on a 2D DP grid it allows for easy-to-understand visualizations where fewer coloured pixels (visited states) usually imply faster algorithms. This not only makes it easier to teach these algorithms to students but also helps with debugging and improving performance: an image makes it easy to understand the structure of an alignment and to spot bottlenecks in algorithms.

Status: This work package is done and used for e.g. Figure 2. Visualizations will be added as new methods are developed.

WP3: Benchmarking aligners Link to heading

A good understanding of the performance trade-offs of existing aligners is needed in order to improve on them. While all recent papers presenting aligners contain benchmarks comparing them in some specific setting, there is no thorough recent overview of tools that compares runtime and accuracy on all of the following properties:

- input type: either random or human,

- error type: uniform or long indels,

- error rate,

- sequence length,

- cost model: unit costs, linear costs, or affine costs,

- algorithm parameters,

- heuristics for approximate results.

For example, Edlib (Šošić and Šikić 2017) lacks a comparison on non-random data, whereas the \(O(n+s^2)\) expected runtime WFA (Marco-Sola et al. 2021) is only benchmarked against \(O(n^2)\) algorithms for exact affine-cost alignment, and not against \(O(ns)\) algorithms. In fact, no efficient \(O(ns)\) affine-cost aligner had been implemented until Daniel Liu and I recently improved KSW2. Furthermore, unit-cost alignment and affine-cost alignment are usually considered as distinct problems, and no comparison has been made about the performance penalty of switching from the simpler unit-cost alignments to more advanced affine costs.

Status: The implementation part of this work package is done and used to benchmark A*PA and make figure Figure 1. A thorough comparison of tools is still pending.

WP4: Theory review Link to heading

There is no review paper of exact global alignment methods. Navarro (2001) seems to be the most relevant, but focuses on semi-global alignment (approximate string matching) instead. Either way, there has been a lot of progress since that paper was published:

- computer hardware has improved, allowing for SIMD based methods,

- new recurrence relations have been found (Suzuki and Kasahara 2018),

- new algorithms have been implemented (KSW2, WFA, Edlib, block aligner).

Thus, the time is right for a new review summarizing both the various algorithms and implementation strategies used in modern pairwise aligners. This would also include a discussion of implicit previous uses of A* and heuristics, and how changing to an equivalent cost model can have an effect equivalent to using a heuristic.

Status: Most of the literature has been summarized in a blog post as part of the background research for A*PA. A dedicated paper has not yet been started.

WP5: A*PA v2: efficient implementation Link to heading

The biggest bottleneck of the current A*-based implementation is the need to store information for each visited state in a hashmap and priority queue. Each visited state has to go through the following process:

- Check if it was already expanded before in the hashmap.

- Evaluate the heuristic.

- Push it on the priority queue.

- Pop it from the priority queue.

- Evaluate the heuristic again.

- Update the hashmap.

It turns out that this is up to \(100\) times slower per state than Edlib, which only stores \(2\) bits per state and can compute \(32\) states at a time using bit-packing.

To speed up A*PA, it will be needed to compute multiple states at once so that bit-packing or SIMD can be used. One way this could work is local doubling. Similar to the band-doubling technique introduced by Ukkonen and used by Edlib (Ukkonen 1985; Šošić and Šikić 2017), it is possible to efficiently process states column-by-column and revisit previous columns when it turns out more states need to be computed.

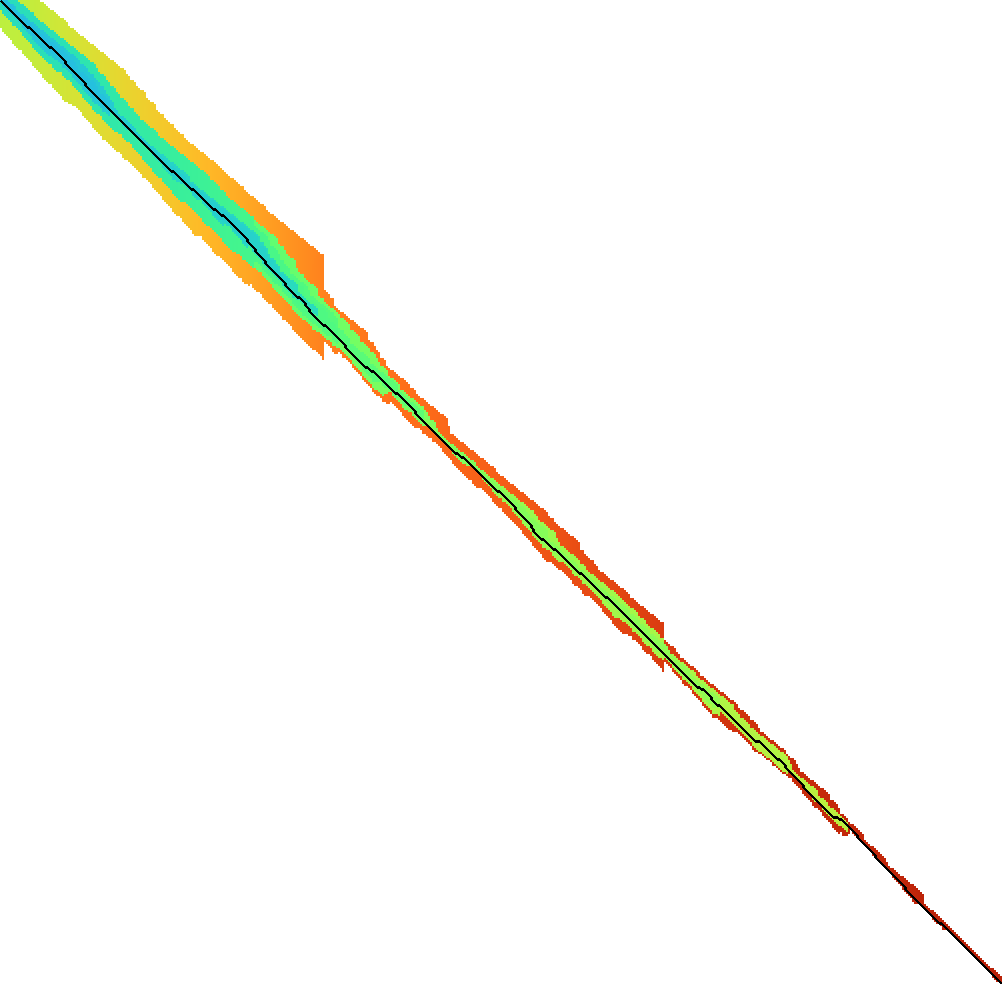

It works by choosing some threshold \(f\) and computing all states \(u\) with \(f(u) := g(u) + h(u) \leq f\) from left to right (column by column). When a column has no states with \(f(u) \leq f\), this means that the distance between the two strings is more than \(f\), and the threshold must grow. Ignoring pruning, this would work roughly as follows:

- For each column \(i\) store the last value of \(f_i\), which starts at the value of the heuristic in \(0\), and store the last increment per column \(\Delta_i\) which starts at \(1\).

- For increasing \(i\) starting at \(0\), find the range of column \(i\) with \(f(u) \leq f_i\) and compute the distance to these cells.

- As soon as the range is empty for some column, backtrack and double the band for

previous columns:

- For \(j\) going down from \(i-1\), add \(\Delta_{j}\) to \(f_{j}\) and double \(\Delta_{j}\).

- When \(f_{j-1} \geq f_{j}\), stop decreasing \(j\) further.

- Now continue with step 2, increasing \(i\) starting at \(i=j\).

The result of this process can be seen in Figure 5. Note that this does not yet account for pruning, where some difficulties remain to be solved. In particular, the algorithm relies on the fact that doubling \(\Delta_i\) roughly doubles the computed band. Since pruning changes the value of the heuristic, this is not true anymore, and the band often grows only slightly. This breaks the exponential doubling and hence causes unnecessarily large runtimes. A possible way to improve this could be enforce at least a doubling of the computed band.

In the current implementation, computing the heuristic at the top and bottom of each band (to find the range where \(f(u) \leq f_i\)) and storing the computed values for each column require a lot of overhead. Using blocks of columns as in block aligner (Liu and Steinegger 2023) could significantly reduce this, since then the bookkeeping would only be needed once every \(8\) to \(32\) columns.

Figure 5: Expanded states with local doubling.

It is still an open problem to find an efficient doubling strategy when pruning is enabled, but even without that or other optimizations this method has already shown up to \(5\times\) speedups, and I expect that a solution to the pruning will be found.

Status: The local-doubling idea as explained above has been implemented with some first results. Moving to a block-based approach and switching to a SIMD-based implementation is pending.

WP6: Affine costs Link to heading

Similar to how WFA (Marco-Sola et al. 2021) generalized the diagonal-transition method (Ukkonen 1985; Myers 1986) to affine gap-costs, it would increase the applicability of A*PA if it is generalized to affine gap-costs as well.

There are two parts to this. First, the underlying alignment graph needs to be changed to include multiple layers, as introduced by Gotoh (1982) and used by Marco-Sola et al. (2021). This is straightforward and can be reused from the re-implementation of Needleman-Wunsch for affine-cost alignments.

Secondly, and more challenging, the heuristic needs to be updated to account for the gap-open costs. One option would be to simply omit the gap-open costs from the heuristic and reuse the existing implementation for unit-costs, but this limits the accuracy. In particular when the gap-open cost is large, at least \(4\) in case of substitution and extend cost \(1\), the heuristic can become much stronger and could correctly predict the long indels. This will make aligning sequences with such long indels much faster.

The main hurdle to be taken is to efficiently implement the updated computation. Having \(3\) (or more) layers increases the number of cases that must be handled, and changes the specific structure of the gap-cost chaining seed heuristic (GCSH) that we currently exploit for its relatively simple and efficient computation.

Despite these complications, I expect that it will be possible efficiently compute the affine heuristics. It will probably require new, more complicated algorithms, but first experiments show that there is still a lot of structure in the layers (see Groot Koerkamp and Ivanov (2024)) of the heuristic that can likely be used to efficiently compute it.

Status: Some thought has been given to the efficient computation of affine heuristics, but without concrete results so far.

WP7: Ends-free alignment and mapping Link to heading

Besides global alignment, another very relevant problem is semi-global alignment, where one sequence is aligned to a subsequence of another sequence. This is particularly relevant in the context of mapping, where multiple reads are semi-globally aligned to a single reference. This is particularly relevant in genome assembly, where a genome is being assembled from a set of overlapping reads.

There are many tools that solve this in an approximate (inexact) way, with Minimap (Li 2016, 2018) being one popular approach that merges multiple ideas such as hashing, as used in BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990), and MinHash sketching (Broder 1997). Exact methods such as Landau and Vishkin (1989) are not used, because they are much slower.

Supporting semi-global and more generally end-free alignment in A*PA should be relatively straightforward by adjusting the heuristic to allow the alignment to end anywhere on the bottom and/or right border of the alignment grid, instead of only in the exact bottom-right corner.

For mapping, the goal is to align multiple short reads (length \(n\)) to a single much longer reference (length \(m\gg n\)) in time near-linear in \(n\), as opposed to time near-linear in \(n+m\). This will require new ways to find seeds and matches, as the reference can only be indexed once up-front, and having \(O(m)\) matches must be prevented. Furthermore this will require ways to ensure that aligning the read is only attempted around matches. In a way, the building of the heuristic and the underlying alignment graph must be lazy to ensure that no redundant work is done.

This will likely require significant updates to the A*PA infrastructure that cannot be foreseen right now.

Status: Semi-global alignment should be straightforward, but mapping will require further research that has not been started yet.

WP8: Further extension and open ended research Link to heading

In case there is time left after the previous work packages, or it turns out some of them cannot be done, there are further research questions that are interesting to work on. When above things don’t work out, here’s more options. This open ended research could be on various topics.

- Further extending A*PA

Approximate alignment: A* only guarantees to find a shortest path when an admissible heuristic is used that is a lower bound on the actual distance. It may be possible to come up with inadmissible heuristics that give up this property. This could lead to faster alignments, at the cost of losing the exactness guarantee.

Status: Not started.

Using a candidate alignment: The local-doubling technique described in WP5 could be optimized further by using a candidate alignment. The algorithm can then prove that the candidate alignment is indeed correct using the known cost of the path and sequence of matches on the path: It is know in advance which matches will be pruned, and what the required value of \(f=f_i\) is in each column. This enables us to pre-prune some matches in advance and then run the algorithm once from start to end, without the need for backtracking and growing of the band. The only drawback is that in case the candidate alignment overestimated the minimal cost by \(x\), the algorithm will waste \(O(x\cdot n)\) time on states that could have been avoided. However, the possible \(2\times\) speedup gained by not have to backtrack may make this optimization worthwhile.

Status: Some initial ideas. Experiments already showed a \(3\times\) speedup over A*PA (v1) using a non-optimized naive implementation.

- A* for RNA folding

- RNA folding is a classical cubic DP task that seeks to find the folding of an

RNA sequence that minimizes the free energy, or equivalently, maximizes the

number of bonds between complementary bases. Exact methods such as

RNAfold tend to be slow and cannot efficiently handle sequences longer

than \(10000\) bp (Lorenz et al. 2011).

It may be possible to use A* on this problem by creating a heuristic that can penalize bad potential fold candidates.

Status: Some initial experimenting has been done but not yet been successful. One bottleneck seems to be that the optimal score of a structured fold is relatively close to the optimal folding score of a random RNA sequence, which makes it hard to penalize regions that don’t fold well.

- Pruning A* heuristic for real-world route planning

- Navigation is one of the big applications of A*, where a simple

Euclidean-distance heuristic can be used.

A lot of research has been done to speed up navigation, including

e.g. precomputing shortest paths between important nodes.

It may be possible to apply pruning in this setting. At a high level, the idea is as follows. The Euclidean-distance heuristic simply takes the remaining distance to the target and divides it by the maximum speed. In this setting, highways are somewhat analogous to matches of seeds: an efficient way to traverse the graph. A lack of highway, and similarly a lack of matches, incurs a cost. Thus, as soon as a shortest path to some stretch of highway has been found, this stretch can be omitted for purposes of computing the heuristic. As the amount of remaining highway decreases, it may be possible to efficiently increase the value of the heuristic in places that depend on this road.

One way this may be possible is by first running a search on the graph of highways only, and then building a heuristic that sums the distance to the nearest highway and the highway-only distances. As the number of remaining highways decreases it may be possible to dynamically update this heuristic and penalize states lagging behind the tip.

Status: Not started apart from the high level ideas described above.

- Genome assembly using A*

- Genome assembly is a big problem in bioinformatics with many recent advances

(e.g. Rautiainen et al. (2023)).

Various algorithms and data structures are being used, but many pipelines

involve ad-hoc steps.

I would like to better understand these algorithms and see if it is possible to formulate a formal mathematical definition of the assembly problem, with the goal of minimizing some cost. Then, it may be possible to solve this exactly by using an A* based mapping algorithm (WP7).

Status: Not started.

WP9: Thesis writing Link to heading

I will end my PhD by writing a thesis that covers all results from the work packages above.

Publication plan Link to heading

I plan to write the following papers, to be submitted to BioInformatics or RECOMB unless stated otherwise.

- WP1: A*PA v1

- This is work in progress and already available as preprint (Groot Koerkamp and Ivanov 2024), together with Pesho Ivanov

- WP2: Visualization

- This will not be a standalone paper, but will be used to create figures for other papers such as the A*PA paper and the theoretical review of algorithms.

- WP3: Benchmarking

- This will be a publication together with Daniel Liu benchmarking existing and new aligners on various datasets. It will compare both runtime and accuracy (for inexact methods).

- WP4: Theory review

- This will be a publication that discusses algorithms and optimizations used by the various tools, including theoretical complexity analyses and methods for more efficient implementations. This may be submitted to Theoretical Computer Science instead of BioInformatics, and will be in collaboration with Pesho Ivanov.

- WP5: A*PA v2: efficient implementation

- This will be a shorter paper that builds on the v1 paper and speeds up A*PA significantly.

- WP6: affine costs

- The results of this WP will likely be presented jointly with WP7.

- WP7: semi-global alignment

- This will be an incremental paper that compares A*PA to other aligners for mapping and semi-global alignment.

- WP8: extensions

- In case I find further optimizations and extensions for A*PA, they will be collected into an additional paper, or possibly presented together with the previous WPs.

Time schedule Link to heading

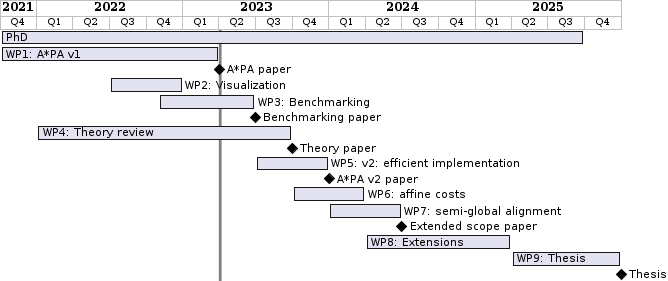

The planned time for each work package is listed in the figure below. Diamonds mark planned papers.

References Link to heading

Teaching responsibilities Link to heading

Teaching will take half a day to a full day a week. So far I have been a TA for Datastructures for Population Scale Genomics twice, and I plan to do this again in upcoming fall semesters. I have made multiple (interactive) visualizations (suffix array construction, Burrows-Wheeler transform) for this course that can be reused in next years. Currently I am helping with our groups seminar.

Other duties Link to heading

Outside my PhD time, I am involved in the BAPC and NWERC programming contests as a jury member.

Study plan Link to heading

I plan to take the following courses:

| Course | EC | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Graph Algorithms and Optimization | 10 | Currently enrolled |

| Poster presentation at IGGSY | 1 | Done |

| Transferable skills course, likely Ethics, Science and Scientific Integrity | 1 | Later |

| Academic paper writing | 2 | Optional |

Signatures Link to heading

- Supervisor:

- Second advisor:

- Doctoral student:

- Date: March 2 2023